Credits: Cover photo by Chris Charles

When we decided to go to see orangutans in the wild, we didn’t hold any particular perception of the orange apes.

Chimpanzees and gorillas were more deeply embedded in our consciousness, which makes sense when you consider the relatively high exposure we’ve had in our lifetimes. We’ve seen chimps starring in classic cinema like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes, and dozens of other movies, TV shows and advertisements, while their plight later entered widespread public awareness via high-profile, anti-animal testing and cruelty campaigns. Likewise, Gorillas are just there in the culture, showing up in our daily vernacular, as men in monkey suits, and earning sympathy through documentaries like Virunga, or notoriety via King Kong.

Orangutans, on the other hand, have played hardly any leading roles.

Photo Credit: Save Virunga

We didn’t need to dig much to find the most famous teller of orangutan stories though. Biruté Galdikas is one third of the “Trimates”, a trio of protégés of anthropologist Louis Leakey, who each led pioneering studies of great apes in their natural environments.

In 1971, Galdikas, the least known of the three (alongside Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey), traveled to Tanjung Puting in the Indonesian portion of Borneo to study orangutans. Fifty years later, her ongoing research is the world’s longest continuous study of orangutans conducted by one lead investigator.

It’s impossible to imagine where the apes would be today without her work and the subsequent stories she has told to the locals, Indonesian government, global scientific community and international audiences. Her story was the reason we chose to go to Tanjung Puting National Park.

Photo Credit by By Simon Fraser University - University Communications

The Park, we learned, is something of a beacon of hope in amid a landscape of environmental devastation. The jungles of Kalimantan have been subject to decades of mining and logging, much of it illegal, mass deforestation for palm oil plantations and processing plants, and rampant fires. Orangutans have been one of the many victims.

We were dimly aware of the issues, but it was only in actively researching ahead of visiting that we began to understood the extent of the challenges. We were later told that many incoming tourists have no idea about them whatsoever.

That fact is alarming, but not surprising. Back in our home countries, far from the jungle, it’s easy not to be aware. Even if we do educate ourselves, when the reality is not hitting us in the face, it’s so easy to disconnect, lose a sense of urgency, feel confused, or perhaps worst of all, simply forget.

It’s easy too to slip into the mindset that has become the default for most people in modern society: that animals are either attractions, food, possessions or pests, rather than fellow beings walking the earth.

Story Animals

The forest and the orangutans need us to care, now more than ever. They need greater awareness, and ultimately more activists, more eco-tourism, and more donations. We believe more stories, better told, are the first crucial step to making that happen.

“I think it’s very important for scientists to get out there and speak to the public. Go and talk to people. Sit in front of zoo cages and talk to what’s happening to the animals in the wild that are represented in those cages. Just be out there. Do like politicians do and go into people’s living rooms and talk about what’s happening.”

—Biruté Galdikas

Dr Galdikas’ work demonstrate the potential ripple effects of powerful storytelling. It’s one of the most effective weapons in the fight; not just for scientists, but anyone with a compelling tale to tell.

For our part, we wanted to better understand orangutans, to know if there was more to their story than we’ve seen in documentaries.

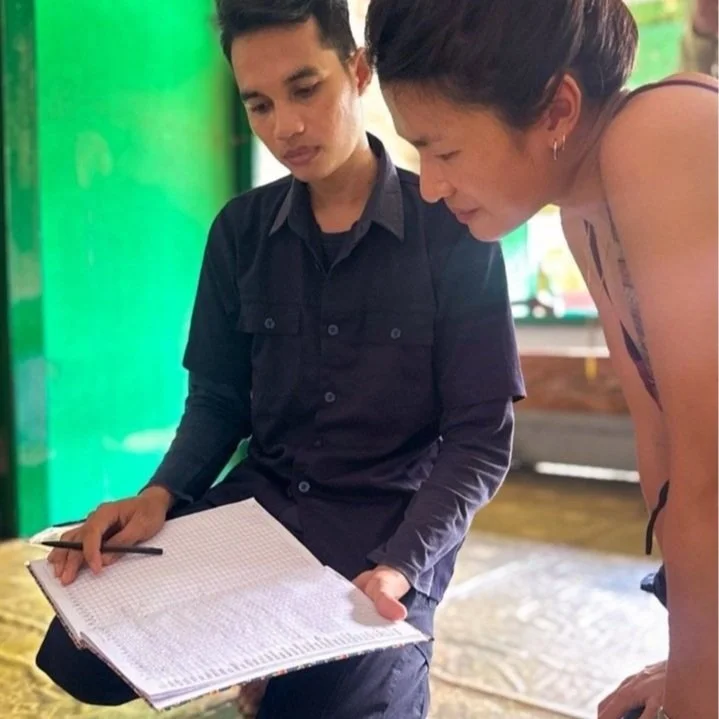

As we scoured the English language internet, we struggled to find the perspectives of people in the community, those who live and work day-in-day out with the apes. We wanted to know about their personal relationships with the forest and orangutans: Had they had memorable experiences interacting? Did they feel the same as we outsiders do, or did they have their own unique perspective?

We were also curious about the folklore of the indigenous people. Did their traditional stories inform their feelings about the orangutans, and nature as a whole today, and could translating and disseminating them bring more depth to our own understanding of the animals and the forest?

The concept of Story Animals was born from a desire to solicit these insights. Perhaps sharing them could play a small part in invoking greater empathy for our orange cousins.

We visited Tanjung Puting in late Spring. While there, we spoke with people at Sekonyer Village and the three camps inside the National Park, in Pasir Panjang near the Orangutan Foundation International (OFI)’s Care Centre & Quarantine, and around the city of Pangkalan Bun.

The interviewees’ lives and livelihoods are intertwined with orangutans. They are fully invested in their plight and we were both touched and inspired by their dedication. We were privileged to sit and hear their stories, and grateful to them for sharing with us the special relationship they have to the forest and the animals.

We discovered that there are indeed many remarkable stories residing in Tanjung Puting. The challenge is getting them out and into the world.

The first obstacle is the lack of any systematic setup or resources for steady and efficient recording of information. The job falls to bilingual volunteers to spend spare time translating documents about the orangutans, the forest, and Dayak culture from Indonesian into English.

There is no existing database of stories. Much is word-of-mouth, passed between people, or down through generations, over time. The rangers, tour guides, villagers, foundation workers and scientists we met tended not to be equipped with pithy pre-packaged anecdotes, and gleaning their stories is usually not a quick and immediate process.

Even if there were such a bank of content, how can it be transmitted to the world without a dedicated marketing team? Funds are limited and allocating what there is to expensive marketing professionals means less for on-the-ground orangutan care.

Meanwhile, would-be storytellers are restricted in the nature of what they are allowed to share. Ideally NGOs would be able to create more impactful content, both online and within camp information centers, giving greater exposure to the environmental destruction and knock-on effects. However, local authorities are highly sensitive and those operating in the park must constantly tread cautiously or risk being shut down.

Photo by Tom Fisk Pexel

Throughout our days in Tanjung Puting, we encountered a surreal day-to-day veneer of harmony concealing a darker side. The rainforest hums with life, yet as our plane had landed at Pangkalan Bun, we’d witnessed vast palm plantations sprawling ominously into the distant mist. The National Park is an island in a sea of palm oil. Interviewees put on a positive face, yet the impacts of deforestation lurked closely in the shadows of almost every conversation.

The forest is the beginning, middle and end of the story. Everything is connected. The forest depends on the orangutans, the jungle’s keystone species, who eat the fruit and spread seeds. With less forest, there is not enough food, and with no corridors between patches of rainforest, orangutans are crammed perilously close together, forcing them to fight over fruit, and expend vital energy.

We may not have much time left. Though we don’t know exact numbers, it’s believed that the Borneo orangutan population has declined by 50% in the last five decades. With eight or nine years between birth cycles, they reproduce too slowly to bounce back. Unless the situation improves, predictions are they will disappear in the wild within the next 50 years.

We’d be losing them while their story is still being written. There’s still much we don’t know and we’re gaining new knowledge all the time. We put together a brief fact-file of some of the most intriguing things we learned along the way.

We heard time and again about the similarities between orangutans and humans, and the empathy that comes with it. Once you get close with them, it’s hard to turn away. Since few people will ever have the opportunity for such an intimate interaction, it’s up to the storytellers, locally and across the globe, to help us all to connect.

- Yanyie & Chris